We have touched upon the Japanese side being challenged with internal buy-in/alignment for Australia, and the Australian side on the “customized approach” to Japan or Japanese corporates. While these issues can be anticipated and planned for, unexpected situations always arise. Hence, the actual engagement will become a valuable experience for understanding each other. This Part III (the final part in the series) intends to put a spotlight on how Japanese corporations can engage with Australian universities and research institutes. These institutions offer a wealth of untapped potential and represent a rich source of capabilities Japanese corporations can leverage off, and frankly less explored at this stage.

The wider objective of this piece is our contribution to a conversation about increasing the A-J innovation success cases in the Australia-Japan corridor. Specifically, IGPI shares some of its observations of how Japanese corporates can engage or partner with Australian universities and research institutes – these could be in the forms of straightforward research relationships all the way to commercialization initiatives.

Throughout the article series, we have touched on the changing nature of “What” and “Who” Japanese corporations are collaborating with in the Australia-Japan corridor. We explored the capabilities of the broader Australian innovation ecosystem, including universities and research institutes.

However, we also highlighted that both Japanese and Australian sides need to prepare internally before engaging. For Japanese corporations, this involves internal alignment between headquarters and the local arm. For Australians, it means developing a customized Japan strategy to understand and overcome cultural or communication barriers.

You can find Part I can be found here and Part II here.

The next question is “how,” or in other words, the “actions” to take for collaboration.

It is first important to note that it is common for Australian universities to have a dedicated department for managing industry collaboration and IP-related matters (e.g. commercialization). These departments are generally known as “Technology Transfer Offices” or TTOs1.

TTO is a general term, and some universities might call it an “Industry Engagement Office” or something similar. TTOs are a crucial point of engagement for any industry partner, regardless of whether they have existing connections with university faculty. This is because the university’s IP management and contractual matters will ultimately be handled by the TTO. Therefore, establishing a holistic relationship with the university early on is important and beneficial.

From the Australian perspective, identifying the right contact within a Japanese corporation is essential. However, this is easier said than done since, unlike Australian universities with their standardized TTO function, Japanese corporate structures vary significantly. To get started, having a Japanese engagement specialist is helpful. If this expertise is not accessible internally, then engaging with government bodies (like Austrade in Japan) or ecosystem participants (like IGPI) can be a strong starting point for your Australia-Japan innovation journey.

Once you know who to contact, the next step is exploring engagement and partnership options. Here are some collaboration methods Japanese corporations and Australian universities can potentially explore (but not limited to):

2.1. Example of Mode of Collab. # 1: Contract Research

Contract research offers a tailored approach for Japanese corporations to access expertise from Australian universities on specific research topics. This could include, consulting, evaluations, lab services, or independent research projects2. The scope is flexible and can range from simple research outsourcing to joint research projects led or supported by the university. However, contract research is generally considered a transactional engagement rather than a long-term partnership, though it can be a stepping stone. It’s a valuable way for Japanese corporations in Australia to gain first-hand experience with a university’s research capabilities.

2.2. Example of Mode of Collab. # 2: Center of Excellence (CoE)

Center of Excellence (CoE) is a generic term referring to hubs that have specialized units (or individuals, or even collaborations between organizations) focused on a particular area of expertise3. While not exclusively research-focused, CoEs can be instrumental in driving business or industry transformation.

There are already examples of CoEs in Australia with Japanese participants.

| CoE | Brief Example |

|---|---|

| ARC Centre of Excellence in Quantum Biotechnology x Olympus | The Arc Centre of Excellence in Quantum Biotechnology’s focus is partnering with industry and government to seek to drive fundamental understanding and innovation across manufacturing, clean energy, agriculture, health and national security4. |

Unlike contract research, a CoE represents a deeper commercial and technical collaboration on a focus area between the partners.

2.3. Example of Mode of Collab. # 3: Intellectual Property (IP) utilisation

Compared to the previous examples, utilizing intellectual property (IP) offers a more direct and relatively immediate path to commercialization. There are several ways universities utilize IP, and Japanese corporations could be involved with5:

| [1] | Licensing to external companies (i.e. university owns IP, Japanese corporations pay for the IP usage) | |

| [2] | License assignment or selling/buying the IP (i.e. IP’s ownership is sold to third party) | |

| [3] | Create a spin-off company to utilize the IP (different to licensing, as spin-offs generally act as an extension of the university as explained in the Part II article) |

Methods [1] and [2] are straightforward in concept. However, spin-offs can involve Japanese corporations co-establishing the spin-off, also known as “Joint Venture Spin-off / Spin-out” or JVSO. While not uncommon, JVSO offer practical advantages. The industry partner becomes a part-owner and can influence the entrepreneurial mindset and commercial direction of the spin-off. It could also benefit the venture’s credibility and stability with the support of the industry partner too6.

These are just a few examples of how to engage and partner with universities or research institutes. The most suitable method will depend on each partnership’s objectives, timing and situation.

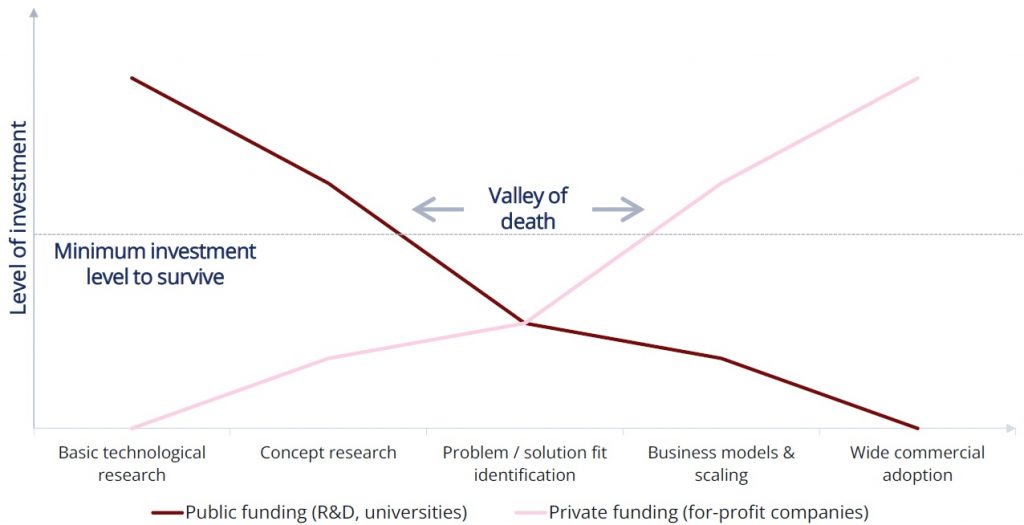

In this article series, we have covered the bottlenecks on the Japanese and Australian sides, and explored various forms of engagement or partnership the two parties can action. But it is important to note that there is a critical gap to be addressed for innovation to reach the real-world, this is commonly known as the “Innovation Valley of Death” (hereafter Valley of Death).

The Valley of Death refers to the timing where public funding (i.e. university funds) for research decreases, but there isn’t enough private fundings (i.e. industry partner support) to reach the minimum investment level needed to sustain the initiative7.

Graph 1: Idea to Value – The Innovation Valley of Death8

Here is a simple scenario to illustrate the Valley of Death:

| 1 | An innovative technology, heavily supported by university on the primary R&D funding, reaches the point where it is proven in a lab environment | |

| 2 | The next step is to test it in the real-world and investigate the problem/solution fit | |

| 3 | At this point, primary research funding from the university starts to diminish as the project nears its conclusion | |

| 4 | But industry players are not ready to invest due to uncertainty about the technology’s business scalability | |

| 5 | As a result, the funding/investment level may be insufficient to support the technology’s commercialization |

The above is an example where R&D is run by a separate entity (i.e. university). However, the same principle applies to internal corporate R&D and new business creation cases as well. For example, the initial R&D might be conducted, but further for scaling could be withheld due to core the business being prioritized or facing challenges that require those funds.

Also, it is noted that Australia is experiencing “publishing inflation”, where researchers are prioritizing the number of papers published over the impact of that paper/research9. This suggests an entrepreneurial mindset focused on commercialization might be lacking or not prioritized. While university professors and TTOs are aware of this issue and working to address it, change cannot happen overnight.

Despite these challenges, it is critical to outline that a smooth transition from the R&D to scaling / commercialization, enabled by sufficient collaborative funding or support is a vital requirement for any innovation to succeed.

For specific/apt Australian innovations that may appeal to Japanese corporations – to avoid the Valley of Death, several factors are crucial. The “Why?”, “What?” and “How?” of the Australian innovation must be (i) well-defined within an international context and (ii) discovered and identified by the right audience (e.g. Japan Inc.) and (iii) aligned with the right market situation and timing. And this is where IGPI Group can add value.

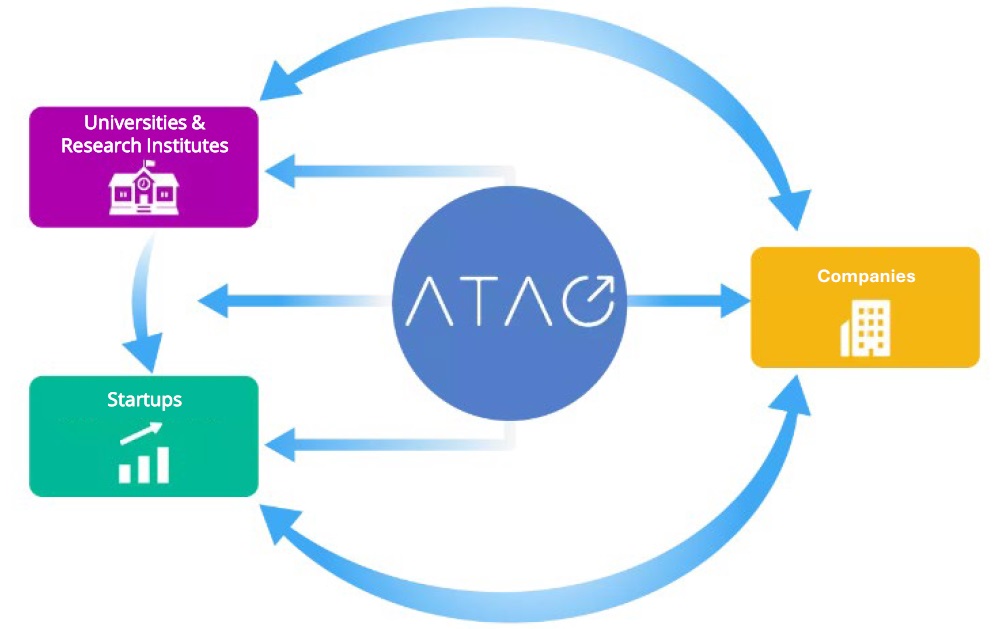

IGPI Group has been working with universities and corporations in Japan to address this issue of innovation commercialization by setting up a subsidiary entity “Advanced Technology Acceleration Corporation”, in short ATAC.

ATAC’s focus is being the bridge to support universities and research institutes, start-ups and Japanese corporations to perform hands-on incubation of cutting-edge technologies, bringing them to the real world based on market needs.

Figure 1: Diagram on ATAC’s support10

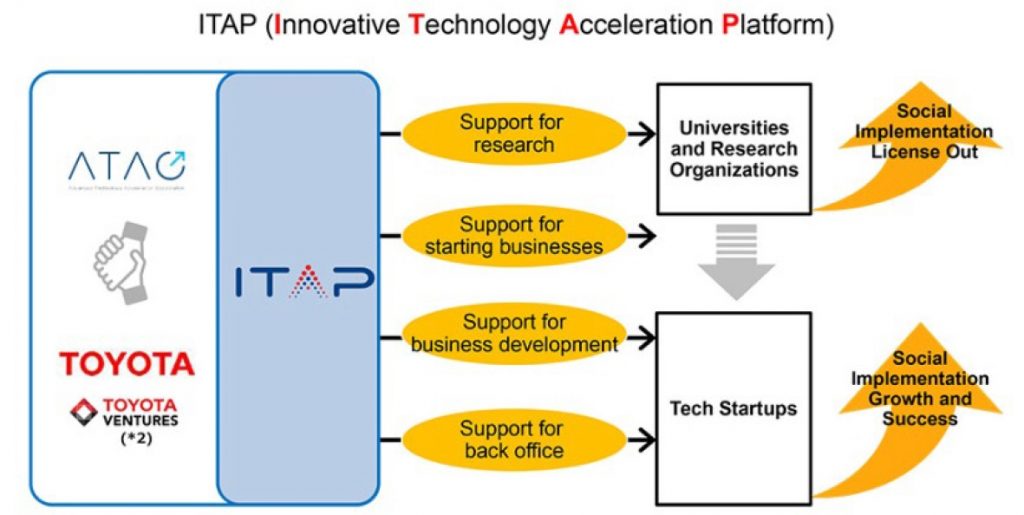

So far, IGPI Group has executed these initiatives for both Japanese corporations or individual Japanese universities. One example is a joint initiative with Toyota Motor Corporation to establish the “Innovative Technology Acceleration Platform” or ITAP, which collaborates with University of Tokyo’s School of Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology and Nagoya University on technology incubation11.

Figure 2: Toyota Global Newsroom12

Another example is a joint initiative with Nagoya Institute of Technology called “Nagoya Institute of Technology Expansion Platform” or NITEP, which specializes in incubating and commercializing the university’s expertise13.

These are just a few examples from Japan, but symbolizes a strong commitment to hands-on incubation and bringing innovation beyond the labs and to the real world through collaboration—literally “Bridge the Valley of Death”. IGPI Group has developed a deep-rooted understanding of innovation ecosystem and incubation processes and we see strong potential for applying our learnings in the Australia-Japan corridor too.

If you are an Australian university or research institute or an Australia corporation that has the ambition of building new businesses through Australia-Japan innovation, we will be glad to have a confidential conversation. IGPI provides highly customized business advisory to its diverse range of clients, including but not limited to:

I. Building your “for Japan” or “with Japan” strategy

II. Capability statement prioritization based on needs/wants of Japan Inc.

III. Market assessment for specific research initiatives x Japan as a market or Japan Inc.

IV. Strategic partner/capabilities search x Japan

V. Commercial negotiations support

VI. Other custom hands-on support (for/in Japan) etc.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

1 Knowledge Commercialisation Australasia – https://techtransfer.org.au/ipc-training/commercialisation/who-participates-in-commercialising-universities-ip/

2 University of Melbourne Contract research – https://research.unimelb.edu.au/partnerships/collaborate/research-collaboration/contract-research

3 Catalant Everything you need to know about CoE – https://catalant.com/coe-everything-you-need-to-know-about-centers-of-excellence/

4 The University of Queensland – https://smp.uq.edu.au/research/research-centres/arc-centre-excellence-quantum-biotechnology

5 Knowledge Commercialisation Australasia – https://techtransfer.org.au/ipc-training/commercialisation/commercialisation-pathways-and-vehicles/

6 J-Stage Articles – https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jsmeicbtt/2002.1/0/2002.1_77/_article/-char/en

7 Idea to Value – https://www.ideatovalue.com/inno/nickskillicorn/2021/05/the-innovation-valley-of-death/

8 Idea to Value – https://www.ideatovalue.com/inno/nickskillicorn/2021/05/the-innovation-valley-of-death/

9 The Age: We’ve hit peak science, and that’s not good https://www.theage.com.au/national/we-ve-hit-peak-science-and-that-s-not-good-20240116-p5exkb.htmll

10 ATAC website – https://igpi-atac.co.jp/

11 Toyota Global Newsroom – https://global.toyota/en/newsroom/corporate/37000298.html

12 Toyota Global Newsroom – https://global.toyota/en/newsroom/corporate/37000298.html

13 IGPI News – https://www.igpi.co.jp/2020/07/28/news_20200728/

Mr. Rachit Khosla is the Country Manager of IGPI Australia. Rachit is a seasoned strategy consulting professional with over 14 years of experience in leading and executing market entry and growth strategies (both organic and inorganic) and open innovation engagements for Fortune 500 businesses and large MNCs across the Asia Pacific. He has advised clients in a diverse range of industries, including automotive, fin-tech, industrial and manufacturing, med-tech & healthcare, smart cities, construction materials, travel, IT & telecommunications to name a few. Rachit was the former Country Manager and Director for YCP Solidiance (now Japanese-owned) and Founder and CEO of an online B2B marketplace startup for professional advisory services focused on Emerging Markets.

Mr. Kaoru Shingae is a Consultant at IGPI Australia. Prior to joining IGPI, Kaoru worked at Toyota, BMW and Boston Consulting Group, primarily specializing in the Automotive and Mobility sector and with exposure to wider industrial sectors. Kaoru has both internal and external strategy experience with a deep understanding on ‘What’ is most important for all stakeholder’s future. He has end-to-end experience from corporate and enterprise-level planning to all the way down to operational planning. Kaoru is a holistic all-rounder who engages with both strategic and operational stakeholders throughout the company. Past achievements include crisis turnaround plans, long and mid-term vision plans, CEO’s company goal plans and sales & market operational plans plus delivery, to name a few. Kaoru has graduated from The University of Melbourne with a Bachelor of Commerce.

Ms. Devina Hashifah is an Intern at IGPI Australia (Nov 2023 – Feb 2024). Devina graduated with a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of Melbourne, majoring in Marketing and Management. She has previously worked in the financial advisory sector and student consulting organizations, conducting research for clients from the agriculture, renewable energy, microfinance, and media industry.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

Australia has rich innovation capabilities and potential that could yield significant benefits for Australia-Japan (A-J) innovation and even beyond.

The key question is “How to enable Australia?”

This entails fully unlocking the innovation capability and potential that Australia holds. This article intends to put a spotlight on the rich capabilities and the missing link which Australia as a nation faces to spearhead their innovation efforts for Japan in particular.

The wider objective of this piece is to contribute to discussions on increasing successful A-J innovation cases within the Australia-Japan corridor. Specifically, IGPI shares some of its observations of the potential bottlenecks faced by the Australian side – these include challenges in gaining awareness and recognition from the Japanese side in a customized fashion, which by no means have easy fixes.

Australia-Japan relationship has been a longstanding and complementary relationship that started in the form of trading in traditional sectors such as energy, agriculture, and mining.

It was touched upon in part I how this relationship is now evolving in terms of “What” and “Who” in recent years. Examples touched upon were Japan transitioning from traditional fossil fuels to initiatives such as renewable energy generation and hydrogen; and widening the collaboration partners beyond mega corporations to include universities and startups in Australia. It also highlighted the bottlenecks Japanese corporations face, such as “Why Australia?” and their motivation to explore such opportunities, particularly addressing the alignment or misalignment between the HQ and local arm.

For the full article on part I: What are the bottlenecks being experienced on the Japanese side?

However, this does not mean there are no bottlenecks on the Australian side. Australia faces its own bottlenecks as the “Innovation supplier”, providing solutions to the Japanese “demand” side.

For decades, Australia has been a key partner for Japan. As previously discussed in part I, this relationship has now dramatically shifted towards sourcing innovative solutions in various forms from broader players in the Australian innovation ecosystem. Namely, these have been from (i) Startups / Spinoffs, (ii) Universities, and (iii) Research Institutes.

2.1. Startups and Spinoffs

Throughout the world, startups have played a pivotal role in driving innovation.

Australia, recognized as having one of the largest startup ecosystems in the world (9th in the world, 2nd in Asia-Pacific)1, is home to numerous unicorns such as Canva, Atlassian, and Airwallex, to name a few. But most recently, the B2B sector startups have been on the radar of Japanese corporations, showing notable progress in Japan and beyond:

| Collaboration | Brief Example |

|---|---|

| Macnica x icetana | Macnica has secured a strategic stake in icetana, a leading artificial intelligence software developer. As part of this deal, Macnica will assume the role of the exclusive distributor for icetana in the Japanese and Brazilian markets2. |

| JR East Water Business x Hivery | JR East Water Business in collaboration with Hivery, an Australian AI-driven retail tech company, will roll out AI-driven vending machine optimization solutions to 6,000 vending machines across the East Japan Railway’s train stations3. |

Both examples illustrate Japanese corporations leveraging solutions from Australian startups in Japan and beyond.

One unique fact to note is that both icetana and Hivery are startups but started off as spinoffs of an Australian university or a research institute. The term “spinoff” describes a new and separate entity created by the parent entity that holds all or partial shares4. In the context of an Australian university or a research institute, spinoffs are created with the aim to boost entrepreneurial activities to commercialize a certain innovative technology5. In the same line, icetana was spun off from Curtin University (Perth, Western Australia), and Hivery from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (in short CSIRO, Australia’s National scientific research agency).

As these startups and spinoffs aim to commercialize the innovative technology they possess, they represent the significant potential for collaboration with industry partners in technical, business, or financial forms to realize new business opportunities.

2.2. Universities

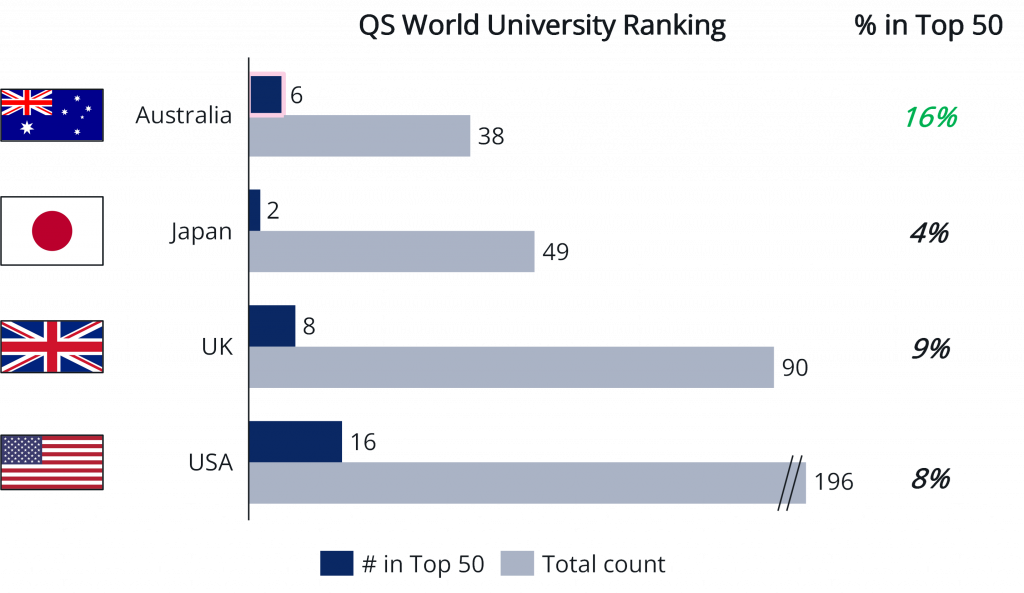

On the other hand, Australia is a rich source of innovation from numerous universities. Australian universities are recognized for their world-class capabilities, comparable to the institutions the USA and UK universities. Based on QS World University Rankings 2025, the composition for Australia, Japan, the UK, and the USA in total count and the count in the “Top 50s” are as follows:

Figure 1: QS World University Rankings 20256

Factually, Australia ranks 3rd in the Top 50 coverage, behind the USA and UK. The interesting fact here is that despite being 3rd, Australia has the highest “coverage ratio” relative to the country’s total university count within the ranking (6 in the top 50 out of a total 38 = 16%; compared to 8% for the USA and 9% for the UK). This highlights the exceptional quality of Australian universities despite being fewer in number.

This excellence is evident in the “International Research Network” metric introduced by the QS World University Ranking in 2024, which provides insights on how internationally connected an institution’s research is as well as recognizing the importance of collaborative research more broadly7.

Here’s how the top 3 Australian universities fare against their counterparts in the USA and UK in terms of international research connectivity:

| Country | International Research Network Score (Top 3 Average) | University | Individual Score | Overall Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 97.2 | The University of Melbourne | 97.4 | 13 |

| The University of Sydney | 95.8 | 18 | ||

| The University of New South Wales | 98.3 | 19 | ||

| USA | 97.5 | MIT | 96 | 1 |

| Harvard University | 99.6 | 4 | ||

| Stanford University | 96.8 | 6 | ||

| UK | 98.9 | Imperial College London | 97.4 | 2 |

| University of Oxford | 100 | 3 | ||

| University of Cambridge | 99.3 | 5 |

Figure 1: QS World UnivTable 1: QS World University Rankings International Research Network Scores8

Again, despite the overall ranking being lower, the research capabilities of the top 3 Australian universities are on par with, or even exceed, those of the leading institutions in the USA and UK. It should be noted that overall ranking includes metrics outside of research capabilities, such as international student ratio, and non-capability specifics.

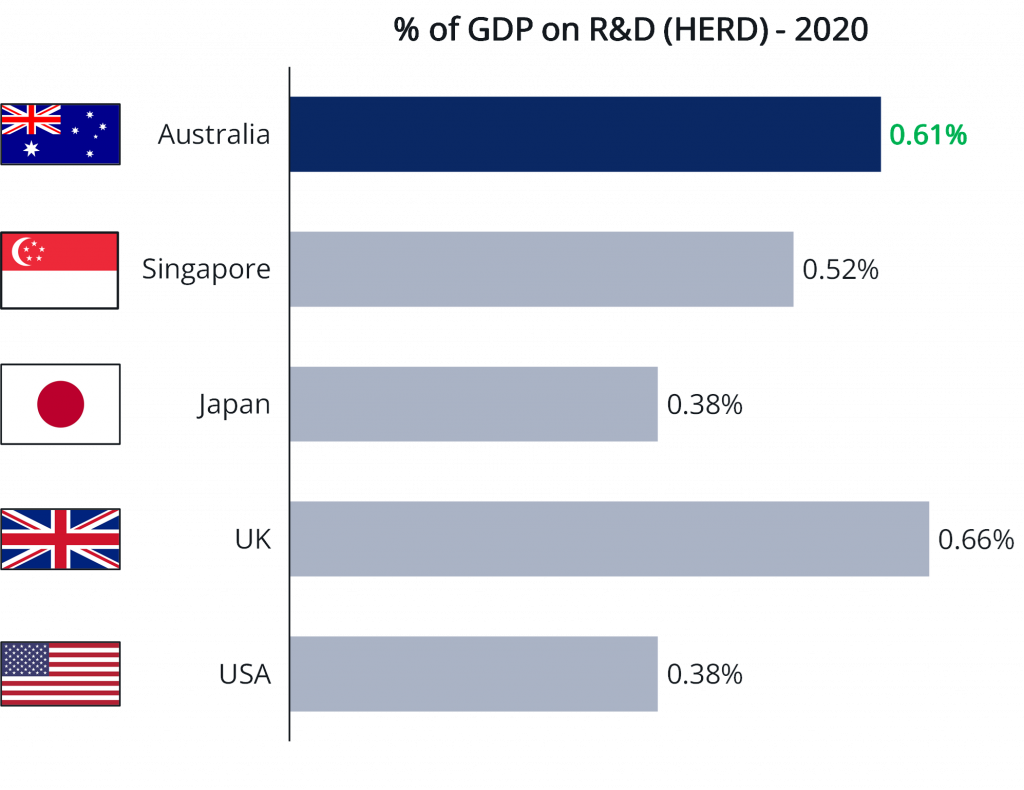

In addition, Australian university’s research and development spending is notably high on a global scale. This is illustrated by the “HERD” or “Higher Education Expenditure on R&D” metric, which measures the R&D expenditure by higher education entities such as universities as a percentage of GDP. Below is a comparison of the USA, UK, Japan and Singapore:

Figure 2: OECD Stat Dataset – Main Science and Technology Indicators Higher-Education Expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP9

| Country | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 0.62% | 0.61%* | 0.62% | 0.64%* | 0.61% |

| Singapore | 0.64% | 0.56% | 0.52% | 0.52% | 0.52% |

| Japan | 0.38% | 0.38% | 0.37% | 0.38% | 0.38% |

| UK | 0.39% | 0.39% | 0.65% | 0.63% | 0.66% |

| USA | 0.36%* | 0.37%* | 0.36%* | 0.36%* | 0.38%* |

Table 2: OECD Stat Dataset – Main Science and Technology Indicators Higher-Education Expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP10

* Note: Estimate (Australia case) or slight definition differs (USA case), Data based on full available data for all 5 listed country comparison

Apart from the UK, which has increased significantly since 2018, Australia is represented with a consistently high level of expenditure or investment into R&D from a GDP percentage basis, which is by contrast, much higher than the likes of the USA or Japan.

Australian universities offer world-class innovation potential, which can be nurtured as business opportunities. The key importance is to make that “critical step” to collaborate with industry partners to realize that capability outside of the lab and apply it to the real world.

2.3. Research Institutes

Separate from universities, Australia also has numerous research institutes. These can be categorized into individual organizations or “Cooperative Research Centers” (hereafter CRC).

Individual organizations can range from national science agencies such as the CSIRO to more niche specialized research institutes (e.g., Health – Melanoma Institute Australia, or even university spinoff R&D entities, etc.).

Most notably, CSIRO is the largest research institute in Australia and one of the significant globally, is often compared to the Australian version of Japan’s “AIST” (産業技術総合研究所) or “RIKEN” (理化学研究所). Typically budgeted with approximately $1.6B AUD annually, it is ranked as the 6th or 7th against selected international applied research organization over the past 10 years and with over 4,000 industry and government partners11. For reference, AIST’s annual expenditure in FY22 was around $1.1B AUD12**. CSIRO’s R&D ranges in 9 fields (further split into subcategories) and works in a collaborative manner with the universities and industries to bring innovation to the real world13.

Figure 3: CSIRO Research fields14

With its broad coverage and extensive network of connections, CSIRO represents the diverse capabilities of Australia’s national science agency.

The other important research institute category is the CRCs. CRCs are Australian government programs since 1990 with the government providing funding support for industry-led collaborations. CRC themes vary depending on each CRC but are all aimed at addressing industry identified problems and key issues. Typically, CRC are mid to long-term programs that can range from 5 to 10 years, but shorter programs (CRC-P) up to 3 years also exist15. CRCs require at least one Australian industry organization and one Australian research organization, but they are not limited in total numbers, and can include non-Australian corporations as partners as well. Below are examples of CRCs that interacted with Japanese corporations:

| CRC x JP Cos | Focus of CRC | Grant size | Collaboration form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Agility CRC x NTT, Yamaha Motor | Support Australian agrifood industry to be profitable and sustainable16 | $50M | Official CRC Partner |

| Future Energy Exports CRC x Impex | Energy export decarbonization17 | $40M | Official CRC Partner |

| Future Energy Exports CRC x JX NOEX, Mitsui O.S. K. Lines, Osaka Gas | Collaboration Conduct research and development to demonstrate the technical feasibility and operability of low-pressure and low temperature solutions for bulk CO2 shipping transport18. | ||

| Heavy Industries Low-carbon Transition (HILT) CRC x Mitsubishi Heavy Industries | De-risk decarbonisation pathways for heavy industry19 | $39M | Official CRC Partner |

Note that entities can be part of the CRC itself (official CRC partner) or engage in a collaborative form, such as the Future Energy Exports CRC with companies like JX NOEX. It is also important to highlight that government grants require the applicants (i.e. CRC lead and partners) to at least match the amount of government grant / funding either through cash and / or in-kind contributions. With both long-term support and commitment, CRCs are unique research initiatives that bring like-minded partners together 20.

While each Australian startup / spinoff, university or research institute faces unique challenges, a common issue is the limited “Awareness” of Australian innovation capabilities. Despite the high quality and rich sources of innovation, Australia’s recognition by Japan lags behind that of global innovation hubs likes of Silicon Valley or Europe.

Unlike the USA or European countries, Japan is a unique country that requires a very different approach culturally or communication wise. Hence from an Australia point of view, applying a global strategy may not necessarily be most effective approach.

IGPI has seen many cases on both the Australian and Japanese sides having basic misunderstandings due to certain cultural differences or communication methods. In particular, the cultural differences can at time cause unnecessary friction unintentionally.

For example, due to the size and organizational structure, Japanese corporations may cause mass communication delays to get to the “Right” person. Even after making contact, an “unwritten” authorization or approval process, known as “Nemawashi”, might be required. This process of consulting stakeholders informally can significantly extend timelines and might be seen as a loss of momentum from a non-Japanese perspective. However, these processes are often integral to Japanese culture, intended to show respect and give courtesy updates to the people who may be impacted by a certain decision, just that it took a bit of time, which may have been out of their control.

To address this type of barrier, it is important for the Australian side to consider a dedicated and specific Japan strategy. This strategy should focus on deepening engagement and forming partnerships with Japan and Japanese corporates. Elements could include prioritizing capabilities that are particularly relevant to Japan, appointing an internal advocate for Japan-related initiatives, and establishing dedicated channels for promotion and interaction with Japanese entities.

It is important to be clear on the details of “what is requested” and “what can be offered as an exchange” from the Australian side to the Japanese side.

Unless there is a clear ambition and direction set for Japan, it could be difficult for both Australian and Japanese side to understand “what is the aim or goal”.

By addressing these bottlenecks with a targeted approach, Australia-Japan collaboration can improve, leading to more successful innovation partnerships across the Australia-Japan corridor.

IGPI Group has developed a deep-rooted understanding of Japanese Corporations and has been a part of the global expansion and ambitions of many prominent companies across the APAC and beyond. If you are an Australian startup, university or research institute, and believe in the potential of Australia-Japan on the pillars of innovation and keen to enhance your approach to Japan / Japanese corporations, we will be glad to have a confidential conversation. IGPI provides highly customized business advisory to its diverse range of clients, including but not limited to:

To find out more about how IGPI can provide consulting support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

1 StartupBlink – Global Startup Ecosystem Ranking

2 icetana – https://www.icetana.ai/investor-updates/global-technology-giant-macnica-takes-strategic-investment-in-icetana

3 Hivery – https://www.csiro.au/en/news/All/Articles/2019/November/hivery-exports-ai-solutions-to-the-world

4 investopedia – https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/spinoff.asp

5 Taylor & Francis Online – https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2086148

6 QS World University Rankings 2025 – https://www.topuniversities.com/world-university-rankings

7 QS World University rankings Methodology – https://www.topuniversities.com/qs-world-university-rankings/methodology

8 QS World University Rankings 2025 – https://www.topuniversities.com/world-university-rankings

9 OECD. Stat – https://data-explorer.oecd.org/

10 OECD. Stat – https://data-explorer.oecd.org/

11 CSIRO Annual report FY22-23 – https://www.csiro.au/en/about/Corporate-governance/annual-reports/22-23-annual-report

12 AIST: Employees and Budget – https://www.aist.go.jp/aist_e/about_aist/facts_figures/fact_figures.html

** RBA Exchange rate at $1 AUD = ¥97 JPY as of 12/08/24

13 CSIRO Research – https://www.csiro.au/en/research

14 CSIRO Research – https://www.csiro.au/en/research

15 Business.gov.au – https://business.gov.au/grants-and-programs/cooperative-research-centres-crc-grants

16 Food Agility CRC – https://www.foodagility.com/about

17 Future Energy Exports CRC – https://www.fenex.org.au/about/

18 Future Energy Exports CRC news – https://www.fenex.org.au/australian-japanese-partners-execute-rd-project-agreement-to-develop-safe-and-efficient-solutions-for-industrial-scale-shipping-of-co2/

19 HILT CRC – https://hiltcrc.com.au/about/

20 Business.gov.au – https://business.gov.au/grants-and-programs/cooperative-research-centres-crc-grants

Mr. Rachit Khosla is the Country Manager of IGPI Australia. Rachit is a seasoned strategy consulting professional with over 14 years’ experience of leading and executing market entry and growth strategy (both organic and inorganic) and open innovation engagements for Fortune 500 businesses and large MNCs across Asia Pacific. He has advised clients in a diverse range of industries including automotive, fin-tech, industrial and manufacturing, med-tech & healthcare, smart cities, construction materials, travel, IT & telecommunications to name a few. Rachit was the

former Country Manager and Director for YCP Solidiance (Japanese owned) and Founder and CEO of an online B2B marketplace startup for professional advisory services focused on Emerging Markets.

Mr. Kaoru Shingae is a Consultant at IGPI Australia. Prior joining IGPI, Kaoru has worked at Toyota, BMW and Boston Consulting Group, primarily specializing in the Automotive and Mobility sector and with exposure to wider industrial sectors. Kaoru has both internal and external strategy experience with deep understanding on ‘What’ is most important for all stakeholder’s future. He has end-to-end experience from corporate and enterprise level planning to all the way down to the operational planning. Kaoru is a holistic all-rounder in engaging with both strategical and operational stakeholders throughout the company. Past achievements include crisis turnaround plans, long and mid-term vision plans, CEO’s company goal plans and sales & market operational plan plus delivery to name a few. Kaoru has graduated from The University of Melbourne with a Bachelor of Commerce.

Ms. Devina Hashifah is an Intern at IGPI Australia (Nov 2023 – Feb 2024). Devina graduated with a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of Melbourne, majoring in Marketing and Management. She has previously worked in the financial advisory sector and student consulting organizations, conducting research for clients from the agriculture, renewable energy, microfinance, and media industry.

Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI) is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & investment firm headquartered in Tokyo with offices in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne. IGPI was established in 2007 by former members of Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI has vast experience of supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~7,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

Within the Australia-Japan realm, the “energy-heavy” relationship has evolved across two related dimensions — “what?” and “who?” — with more stakeholders such as universities and startups garnering the limelight. This article intends to put the spotlight on such examples.

The wider objective of this piece is our contribution to a conversation about increasing the A-J innovation success cases in the Australia-Japan corridor. Specifically, IGPI shares some of its observations of the potential bottlenecks faced by the Japanese side between the HQs and local arms of Japanese corporations. These are internal and complex matters that by no means have easy fixes.

It is no secret that Japan and Australia have cultivated a longstanding and complementary trading relationship, underscored by traditional sectors such as energy, agriculture, and mining. In 2022, Australia contributed to Japan’s resources by supplying Japan with 43% of its liquefied natural gas (LNG) and 66% of its coal, with a predominant share of 75% in thermal coal[1]. On the other side, 7% of total Australian imports comes from Japan, including vehicles, machineries, and electronics (as of Dec 2023)[2]. Japan and Australia have built their relationship on comparative advantages, with Australia serving as a raw materials supplier and Japan as a manufactured goods producer[3].

The nature of the “energy-heavy” partnership between Australia and Japan is evolving in two related dimensions — these are “what?” and “who?” referring to needs and players, respectively.

2.1. Evolving Needs (“What”?)

Japan is a highly developed nation but lacking in natural resources, and Australia possesses abundant natural resources that can complement Japan’s requirements. Japan drew up a national strategy to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050[4], which encompasses a systematic transition from traditional fossil fuels to initiatives such as renewable energy generation and hydrogen transportation. While traditional energy sources will continue to play a role in Japan’s energy strategy in the mid-term, the trend towards a long-term transition to decarbonization is steadfast. In this global trend towards decarbonization and a sustainability focus, collaborations between two nations are widening. Some examples:

| “What?” | Brief Example |

|---|---|

| From Energy to Technology | Although energy remains a high focal point for now, the collaboration paradigm has evolved from traditional resources like coal to a shift towards cutting-edge technologies such as hydrogen transportation. One notable example is LAVO, an Australian energy storage and technology startup that integrated Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enabled digital solutions, which supplied its metal hydride storage technology to the leading Japanese trading house Marubeni Corporation. This will lead to the export of Australian green hydrogen. This collaboration established a precedent as the first of its kind to demonstrate the profitability and safety of exporting Australian renewable hydrogen stored in metal hydride to international market[5]. |

| From Procurement to Co-development | The goal of decarbonization also drives Japan’s investment from procurement to business or technical collaboration for co-developing innovative technologies. Japanese corporations such as JX Nippon Oil & Gas Exploration Corporation, Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, and Osaka Gas have partnered with Australian corporations, including Future Energy Exports CRC, deepC Store, and Low Emission Technology Australia, along with Australian universities such as the University of Western Australia and Curtin University. Together, they have formalized a Project Agreement aimed at collaborative research and development on low-pressure and low-temperature solutions for the bulk transport shipment of CO2. This is to showcase the technical feasibility and operational viability of the solutions and ultimately advancing technologies for the secure and efficient shipment of substantial quantities of CO2[6]. |

2.2. Evolving Partnerships (“Who”?)

The transition of “what” is marked by widening of the players. While mega corporations once held a dominant position, the Australia-Japan collaboration is now witnessing increased participation from innovative participants such as universities and startups.

Australia’s innovation network is characterized by a highly complex yet proactive landscape, where collaborations and partnerships evolve to meet the demands of a rapidly advancing technological era. The collaborative partners between Japan and Australia are in a state of transition from (i) “Corporations x Corporations” to also include (ii) “Corporations x Universities”, (iii) “Corporations x Startups” and (iv) “Universities x Universities”. It symbolizes the growing realization of the strengths of Australian universities and startups, which Japanese corporations can leverage upon for mutual benefit. Some examples:

| “Who?” | Brief Example |

|---|---|

| Corporations x Universities | Macquarie University, a world-leading AI research powerhouse, and Fujitsu, a leading Japanese information and communication technology corporation, have together announced their establishment of AI Research Laboratory at Macquarie University. By utilizing the strengths of each other — the university’s research capabilities and Fujitsu’s generative AI and human sensing technologies — the focus is on researching and developing promising AI applications and related technologies for the society[7]. |

| Corporations x Startups | Morse Micro, an Australian fabless semiconductor startup reinventing Wi-Fi for IoT, secured Series B funding from a consortium of investors led by the Japanese ASIC and system-on-a-chip (SoC) developer MegaChips. Following this investment, MegaChips entered a partnership with Morse Micro to produce compliant semiconductors and modules, offering assurance, sales support, and new distribution channels. This came about because both Morse Micro and MegaChips share a common goal of revolutionizing IoT connectivity by innovating connectivity and establishing robust Wi-Fi HaLow solutions for the future[8]. |

| Universities x Universities | UTS (University of Technology Sydney), with pioneering food tracking technology, has shared the technology to the Wagyu beef farmers in both Australia and Japan. As part of the project Hokkaido University, the partner in the project supported the relationship between Australia and Japan on technology promotion. The project aimed to provide IoT and blockchain-enabled capabilities to the food supply chain market[9]. |

These select examples corroborate the fact that Japanese corporations are increasingly taking note of Australia’s innovation potential. The complementing strengths and common goal synergies can lead to collaboration not only limited to Australia or Japan but in the wider region/world. For this to happen at scale, a long-term view of investment and nurturing is critical. Corporations and stakeholders must actively address these aspects to incubate and support the growth of innovative ideas and technologies.

It is also noteworthy to share that these collaborations take place across diverse sectors and typically are in some combination of business, technical, and financial partnership. Apart from the well-known and time tested (i) “Corporations to Corporations”, some more examples occur across (ii) “Corporations x Universities”, (iii) “Corporations x Startups” and (iv) “Universities x Universities”.

3.1. Corporations x Universities – Examples

| Date | Type | Sector | Japanese Entity | Australian Entity | State | Quick Overview |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sep-23 | Technical | Data Security | NTT | UTS | NSW | NTT and UTS are collaborating to address data security risks collectively, integrating state-of-the-art encryption technology[10]. |

| Jun-23 | Technical | Smart City | NEC Australia | University of Wollongong | NSW | A strategic alliance aimed at jointly spearheading smart city initiatives within the Illawarra region[11]. |

| Apr-23 | Technical | Smart Automotive | IDOM | RMIT | VIC | Collaboration on multiple specialized initiatives dedicated to the advancement of intelligent automotive solutions through the utilization of emerging technologies[12]. |

| Jul-22 | Technical | Carbon Neutrality | Nippon Steel | University of QLD | QLD | Joint research proposal between Nippon Steel and University of QLD aiming to transform CO2 into valuable chemicals through synergistic application of microbial and electrochemical processes[13]. |

| Nov-21 | Technical | Hydrogen | Chiyoda Corporation, ENEOS | QUT | QLD | Jointly announced a ground-breaking achievement of the first-ever successful technological verifications for CO2-free hydrogen to a practical level at scale[14]. |

Table 1. Collaboration between Japanese Corporations and Australian Universities

3.2. Corporations x Startups – Examples

| Date | Type | Sector | Japanese Entity | Australian Entity | State | Quick Overview |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar-23 | Financial | Automated Driving | Suzuki Motors | Applied Electric Vehicles | VIC | Suzuki Motors and Applied Electric Motors Electric Vehicles have signed an MoU to develop an autonomous electric vehicle platform[15]. |

| Oct-22 | Business | AI | Macnica Inc. | icetana | WA | Macnica has secured a strategic stake in icetana, a leading artificial intelligence software developer. As part of this deal, Macnica will assume the role of the exclusive distributor for icetana in the Japanese and Brazilian markets[16]. |

| May-22 | Technical | Engineering Design | Sumitomo Mitsui Construction (SMCC), IHI | Roborigger | WA | SMCC and IHI are collaborating with Roborigger to design and develop the first autonomous tower crane[17]. |

| Dec-21 | Business | Medical | Terumo Corporation | Q-Sera | QLD | Q-Sera, a University of QLD startup, specializing in the development of rapid serum blood collection tube technology, is set to manufacture and deploy its innovation in Japan. This comes after forming a partnership with Terumo Corporation, Japan’s leading medical device company[18]. |

| Dec-19 | Technical | Blockchain | Kansai Electric Power Co Inc. (KEPCO) | Powerledger | WA | Powerledger has expanded its trial in collaboration with KEPCO to facilitate the creation and tracking of Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) as well as solar energy trading[19]. |

Table 2. Collaboration between Japanese Corporations and Australian Startups

3.3. Universities x Universities – Examples

| Date | Type | Sector | Japanese Entity | Australian Entity | State | Quick Overview |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct-23 | Technical | Laser Tech | EX-Fusion, Osaka University | University of Adelaide | SA | The University of Adelaide has partnered with EX-Fusion, a leading Japanese laser fusion startup, and the Institute of Laser Engineering at Osaka University to advance laser technology for clean fusion energy[20]. |

| Nov-22 | Technical | Photovoltaic | Kyoto University, Osaka University | RMIT University | VIC | This project aims to enhance an existing collaborative research network between Australia and Japan to develop next generation solar cells known as perovskite solar cells[21]. |

| Feb-22 | Technical | Telecommun-ications (6G) | Osaka University, Kyushu University | University of Adelaide, RMIT University | SA, VIC | These universities synergize essential capacities to advance 6G telecommunications, addressing the anticipated surge in data traffic by 2030[22]. |

| Jul-21 | Technical | Robotic | University of Tokyo | University of Sydney | NSW | This forum aims to discuss the use of urban robots in public spaces, inviting scholars from Australia and Japan to exchange the latest smart technologies. It also aims to promote ongoing collaboration among researchers in innovation and technology from both countries[23]. |

| May-20 | Technical | Carbon Neutrality | University of Tokyo | University of Queensland | QLD | Realize the goal of “Nanoarchitectured Functional Porous Materials as Adsorbents and Catalysts” to reduce greenhouse gas levels, mitigating global warming and converting them into valuable chemicals[24]. |

Table 3. Collaboration between Japanese Universities and Australian Universities

The nature of Japanese corporation’s associations varies significantly. Regardless of size, corporations may have had extensive length of association with Australia (over multiple decades) or extremely short time. However, the key issue faced in boardrooms is the depth of “Why Australia?” within that corporation and “how motivated” they are to explore such opportunities. IGPI has seen in many cases that the local arm understands the potential on one side but is challenged to convince HQ/RHQ to take any further action (e.g., strategic alignment, etc.). On the other hand, the RHQ/HQ looks at various countries and is not always clear on “Why Australia?” etc., and doesn’t offer much support to the local arm (e.g., funding, human capital dispatch, etc.).

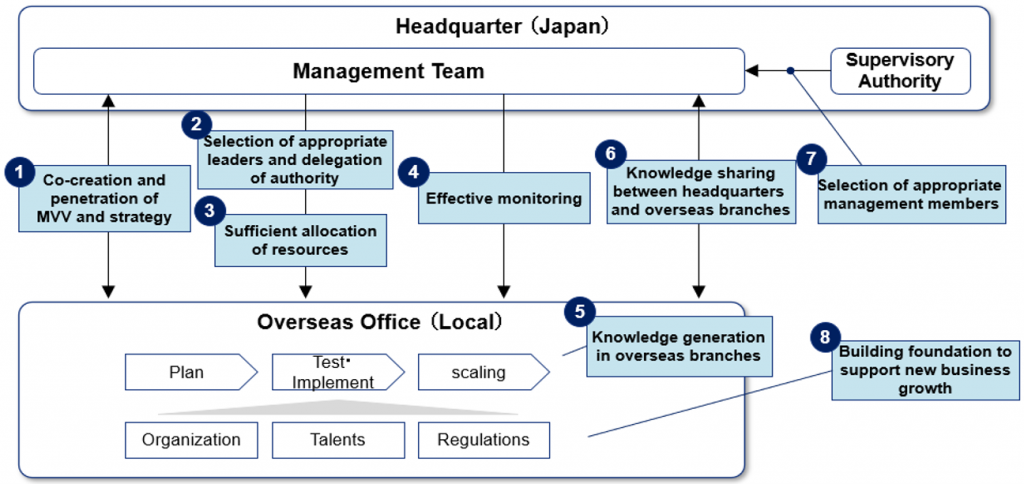

So, the key is addressing these complex and layered internal issues to get the ball rolling. Based on IGPI’s diverse experiences of working with Japanese corporations’ HQs and various in-market offices, as well as supporting JETRO for a case study, there are eight key elements that need to be addressed for smoothly exploring innovation opportunities in a cross-country setting. It usually begins with alignment on strategy, mission, vision, and values (MVVs).

Image: JETRO Case Study Summary Report[25]

Regardless of the Japan or Australia side, unless the counter-country element is identified as part of the future, there will be misalignments, lack of actions, and/or insufficient implementation.

There are notable companies that have already overcome such challenges. For example, companies like NTT and Fujitsu have defined Australia as a “Testbed” market. In NTT’s case, Australia’s unique geographic landscape was perfect for developing next-gen agricultural sensing and communication technologies — with proactive consumers to test new technologies[26]. And in Fujitsu’s case, setting up a “Digital Transformation Center” within Macquarie University in Sydney was to take advantage of the university’s capabilities directly for ideation and co-creation of new solutions for customers — exemplifying the benefits from the diversity of talents[27].

These are examples of “Defining a clear role for Australia”, but high in impact to enable HQ/RHQ and local arm alignment.

IGPI Group has developed a deep-rooted understanding of Japanese corporations and has been a part of the global expansion and ambitions of many prominent companies across APAC and beyond. If you are a Japanese HQ or a local arm and believe in the potential of Australia-Japan based on the pillars of innovation but feel constrained due to any or all of the eight elements in this article, we will be glad to have a confidential conversation. IGPI provides highly customized business advisory to its diverse range of clients, including but not limited to:

To find out more about how IGPI can provide consulting support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

[1] https://japan.embassy.gov.au/tkyo/resources.html

[2] https://tradingeconomics.com/australia/imports

[3] https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/Completed_inquiries/1999-02/japan/report/c05

[4] https://www.meti.go.jp/english/policy/energy_environment/global_warming/roadmap/

[5] https://www.lavo.com.au/blog/marubeni-lavo-exporting-hydrogen

[6] https://www.fenex.org.au/australian-japanese-partners-execute-rd-project-agreement-to-develop-safe-and-efficient-solutions-for-industrial-scale-shipping-of-co2/

[7] https://www.fujitsu.com/au/about/resources/news/press-releases/2023/fujitsu-and-macquarie-university-establish-new-research-lab-to-accelerate-development-of-human-sensing-and-generative-ai-technologies.html

[8] https://www.morsemicro.com/2022/09/06/morse-micro-raises-140m-in-series-b-funding-to-accelerate-iot-connectivity-and-revolutionize-our-digital-future/

[9] https://www.uts.edu.au/about/faculty-engineering-and-information-technology/global-engagement/international-news/tracking-technology-wagyu-beef

[10] https://www.uts.edu.au/about/faculty-engineering-and-information-technology/news/ntt-data-uts-partner-enhance-data-security-research

[11] https://www.uow.edu.au/media/2023/uow-and-nec-australia-join-forces-to-drive-smart-city-innovations-in-the-illawarra-.php

[12] https://idomi.com.au/2023/04/20/idom_rmit_partnership/

[13] https://www.nipponsteel.com/en/news/20220722_100.html

[14] https://www.eneos.co.jp/english/newsrelease/2021/pdf/20211102_01.pdf

[15] https://www.appliedev.com/suzuki-press-release-30-march-2023

[16] https://www.icetana.ai/investor-updates/global-technology-giant-macnica-takes-strategic-investment-in-icetana

[17] https://www.roborigger.com.au/sumitomo-mitsui-construction-teams-with-roborigger/

[18] https://uniquest.com.au/rapid-serum-blood-collection-technology-developed-by-uq-startup-q-sera-to-be-made-in-japan/

[19] https://www.powerledger.io/media/power-ledger-kepco-extend-trial-to-create-and-track-renewable-energy-credits

[20] https://www.adelaide.edu.au/newsroom/news/list/2022/12/14/fusion-of-expertise-aims-to-develop-sovereign-capability.

[21] https://www.dfat.gov.au/people-to-people/foundations-councils-institutes/australia-japan-foundation/grants/2021-22-grantees

[22] https://www.dfat.gov.au/people-to-people/foundations-councils-institutes/australia-japan-foundation/grants/2021-22-grantees

[23] https://www.dfat.gov.au/people-to-people/foundations-councils-institutes/australia-japan-foundation/grants/meet-our-2020-21-grantees

[24] https://japantoday.com/category/tech/first-grant-awarded-under-rio-tinto-australia-japan-collaboration-program

[25] JETRO “Case Study on Management Innovation of Japanese Companies in Southeast Asian Markets and Identification of Key Points” Summary Report

[26] https://www.foodagility.com/posts/australia-the-testbed-for-new-green-iot-technologies

[27] https://corporate-blog.global.fujitsu.com/apac/2019-12-20/digital-transformation-centre-brings-co-creation-to-life-in-australia/

Mr. Rachit Khosla is a seasoned strategy consulting professional with rich experience in leading and executing market entry, growth strategy and open innovation/new business creation engagements for Fortune 500 businesses, large MNCs and Govt. bodies across the Asia Pacific. He has advised clients in diverse industries including green and digital areas. Before joining IGPI, Rachit was the Country Manager at YCP Solidiance, and after that, a co-founder of Conquerem — an online B2B e-bidding platform for boutique consulting firms. Rachit is an avid traveler who has set foot in 40+ countries and lived in 4 countries.

Mr. Kaoru Shingae is a Consultant at IGPI Australia. Prior to joining IGPI, Kaoru worked at Toyota, BMW, and Boston Consulting Group, primarily specializing in the automotive and mobility sector and having exposure to wider industrial sectors. Kaoru has both internal and external strategy experience with a deep understanding of ‘What’ is most important for all stakeholders’ future. He has end-to-end experience in corporate and enterprise-level planning, all the way down to operational planning. Kaoru is a holistic all-rounder who engages with both strategic and operational stakeholders throughout the company. Past achievements include crisis turnaround plans, long and mid-term vision plans, CEO’s company goal plans, and sales & market operational plan plus delivery, to name a few. Kaoru graduated from The University of Melbourne with a Bachelor of Commerce.

Mr. Jiachen Wang is an Intern at IGPI Australia (Nov 2023 – Feb 2024). Jiachen is currently pursuing his Master’s Degree in Finance from the University of Melbourne. Prior to this, he completed an Honours Bachelor of Science from the University of Toronto, majoring in Statistics and Geographic Information Systems. He has had previous internship experiences in the financial sector, spanning equity research, investment banking, and corporate venture capital.

Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI) is a Japan-rooted premium management consulting & investment firm headquartered in Tokyo with offices in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne. IGPI was established in 2007 by former members of Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turnaround projects in Japan. IGPI has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation, to name a few. IGPI has vast experience supporting Fortune 500s, government. agencies, universities, SMEs, and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has approximately 7,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

In recent times, the escalating geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China has revived bipolar dynamics reminiscent of the Cold War, when much of the world became pawns in a superpower competition. Moscow’s aggression against Ukraine has only intensified pressure on developing nations to pick a side between the democratic West and authoritarian China and Russia — a choice that many resist. Meanwhile, a succession of systemic shocks — including the coronavirus pandemic, economic fallout from Ukraine, and deepening climate emergency — have underscored the gross inequities at the core of the world economy and the vulnerability of lower- and middle-income nations to political, economic, and ecological crises not of their own making.[1] Within this, there stands a nation that is uniquely positioned because of its ties to ‘both camps’ that can help bridge the divide potentially like no other — but easier said than done!

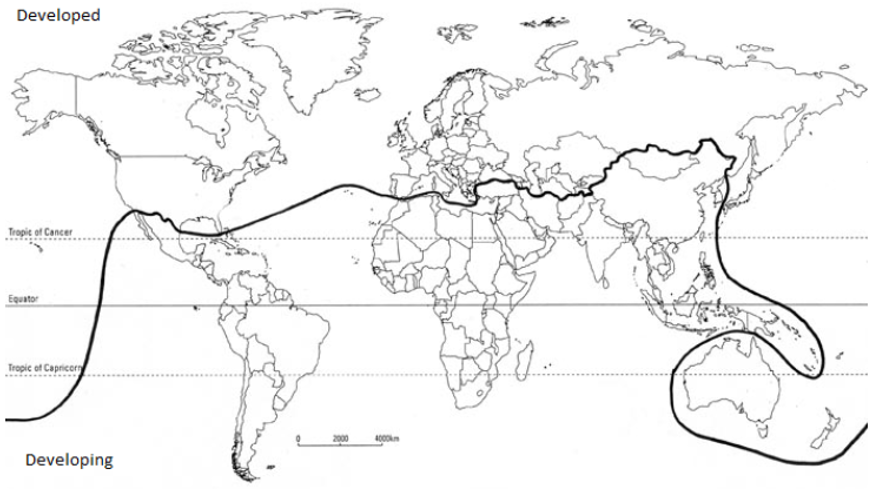

The Global South is a multifaceted concept encompassing geographical, geopolitical, historical, and developmental aspects, with certain exceptions.[2] Used since the late 20th century, the term has seen increased application as we moved into the 21st century. Carl Oglesby, a political activist, is credited with first using “Global South” in 1969. In an article for the liberal Catholic magazine Commonweal, Oglesby discussed how the Vietnam war represented a peak in the North’s dominance over the South. But it was only after the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union — which marked the dissolution of the so-called “Second World” — that the term gained momentum.

The Brandt line, a definition from the 1980s dividing the world into the wealthy north and the poor south.

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1098296 [3]

In a global context, “the North” and “the South” serve as alternative terms for “developed” and “developing” countries, respectively, based on the Brandt line. Together, these terms constitute nearly the entire global population.[4] The two groups are often differentiated by their levels of wealth, economic development, income inequality, democracy, and political and economic freedom, as measured by freedom indices. States that are seen as part of the Global North tend to be wealthier, less unequal, and considered more democratic and developed countries. Southern states are generally poorer, developing countries with younger, more fragile democracies, often reliant on primary sector exports and frequently share a history of colonialism by Northern states.[5] After colonialism, the North continued to maintain unequal trade relationships with the South, which further perpetuated the economic disparities between the regions.[6]

Nevertheless, the divide between the North and the South is often challenged and said to be increasingly incompatible with reality. For example, the differences in the political, economic, and demographic makeup of countries tend to complicate the idea of a monolithic South.[7] How can countries like China and India, each with about 1.4 billion people and GDPs of about $18 trillion and $3.4 trillion, respectively, be lumped together with the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, with a population of a little over 300,000 and a GDP of $984 million, or the southern African country of Zambia with 19 million people and a GDP of $30 billion?[8] Furthermore, globalization has also contested the notion of two distinct economic spheres.

In 2023, many newspaper articles and reports have increasingly referenced the “North-South divide”, predominantly in the context of the war-struck era our planet is experiencing. Illustrating this point, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sparked unity among Western democracies not seen since the first Gulf War. However, the Global South did not meet the Western expectation of global, unified condemnation and action against Russia.[9] As such, the unwillingness of many leading countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America to stand with NATO over the war in Ukraine has brought the term to prominence once again. Global South leaders have been demanding an end to the “plundering international order,” calling for a more representative and responsive global system that caters to the needs of developing economies.[10]

Apart from this, not long ago, the pandemic also posed many challenges for the Global South. The challenges were daunting for a myriad of reasons varying across the diverse countries. They include weak public health systems, lower living standards, and a lack of services in densely concentrated cities or widely dispersed rural populations. Even amongst middle-income countries, whose economies tend to be export-oriented and commodity-dependent, the collapse of global demand puts significant pressure on their national accounts. For some, dependency on tourism and foreign remittances makes up a substantial portion of their GDP, and any losses in these sectors exacerbate unemployment and revenue losses.[11]

From a Japanese lens, the term “Global South” has become such a buzzword that it graces the daily news.[12] Japan has been actively engaging with the Global South, pursuing this engagement through various means such as frequent visits, dialogues, and regional forums, including the G20. Japan’s approach is characterized by its desire to foster a free and open international order, ensure global peace, and address global inequalities.[13]

The North-South divide remains relevant today, as global inequality continues to pose a significant challenge. This divide surrounds economic, social, and environmental disparities.[14] While some countries in the Global South have achieved considerable economic and social progress, others still grapple with poverty and underdevelopment. The divide also influences vulnerability to climate change, with developing countries in the South often facing a disproportionate share of the impacts. Factors such as limited resources for adaptation and mitigation, widespread poverty, and exposure to natural disasters contribute to this vulnerability.[15]

Addressing the North-South divide thus requires a comprehensive and coordinated approach that includes policies to promote sustainable economic development, improve governance and political stability, increase access to education and healthcare, and reduce inequality within and between countries. International cooperation and partnership are also essential for addressing global challenges and promoting equitable development. Although easier said than done, some of the ways to address the North-South divide can include:

To that end, Japan is setting a five-year investment target of more than $13 billion to support developing countries in the Global South, a move that aims to deepen ties with growing, resource-rich economies. The 2 trillion yen ($13.3 billion) in funding would come from investments by Japanese companies backed with government aid, Japan’s Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) stated.[16] As per the then METI Minister Nishimura, “We will strengthen collaboration through support and investments that lead to solutions to societal challenges facing emerging markets, such as carbon reduction and digitalization; Japan aims for ‘win-win’ relationships with the Global South, in which aid leads to economic expansion, local investments by Japanese companies, and export growth.”[17]

Japan’s focus on the Global South brings a ray of light amid an increasingly chaotic global situation.[18] As an example of the themes mentioned above, such as climate change and investment, an initiative that was recently announced is India-Japan Fund (IJF). IJF is a $600 million fund launched by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF). The fund will be supported by JBIC-IG Partners (a JV of JBIC and IGPI) and aims to invest in environmental sustainability and low-carbon emission strategies, focusing on areas such as renewable energy, e-mobility, and waste management.[19] Interestingly, the fund will have almost equal financial contribution from the Japanese and Indian sides, which is significant in the North-South discussion as it brings in connotations of equality — one of the root issues of this historical divide.

From a global North-South lens, Australia’s role in this divide is complex due to its unique position. Geographically located in the Global South, Australia is considered part of the Global North due to its economic and political ties. If we examine Australia further, it is a regional superpower and one of the richest nations in the world,[20] situated in an important and strategic position for Global North allies with Asia-Pacific interests. Its Western-influenced political economy, combined with its relations with many Asian countries provide a unique geopolitical context.[21]

The above makes Australia’s role in the Global North-South divide crucial, and based on Australia’s worldview, including the growing importance of the Global South, Australia can contribute to the world order in a way that matches its interests. Some of the dimensions along which Australia is/can further play a role include economic, environmental, and security aspects, acting as a bridge in the divide:

1. Economic Partnerships and Aid for Development

2. Environmental & Innovation Cooperation

3. Regional Stability, Security & Cooperation

4. Education, Knowledge & Cultural Exchange

It is essential to note that the role of any individual country, including Australia, is complex and multifaceted. Furthermore, we have established that all Global South countries can’t have a ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy due to their diverse global views and progress.

IGPI established its Australian operations in 2020 as we recognized the increasingly prominent role that Australia is playing and can play in APAC and the wider world. Although Australia is not new to corporate Japan, since business relationships go back several decades, the nature of the relationship has been evolving quickly. There are many untapped opportunities waiting to be introduced to the world — based on the fact that Australia has a relatively high quality of innovation,[22] but commercialization of those innovations hasn’t been its strong point. This is one area where Japanese expertise in globalizing businesses can complement Australia in solving global issues. On that note, IGPI supports JETRO’s J-Bridge program, which encompasses open-innovation-driven collaborations between Japanese corporations and Australian companies in their strength areas of “Green” and “Digital”.

Several Australian innovations can potentially solve issues in the Global South. As a public example of the above point with regards to innovation cooperation — Australian insurance company, Hillridge Technology helps farmers lessen the financial impact of adverse weather events by using blockchain technology to immediately and automatically pay out insurance claims as soon as a weather event occurs within a certain distance from a farmer’s operations.[23] Also, Hillridge Co is co-operating with Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Group (MSIG) in Vietnam to launch a new agricultural insurance product that protects farmers in Vietnam from the risks of drought.[24]

In future, IGPI Australia will endeavor to continuously focus on joining more dots between Japan, Australia and the rest of the world through its business pillars of advisory and investments to play its part in making this planet a more cohesive place.

To find out more about how IGPI can provide consulting support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

[1] https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/08/15/term-global-south-is-surging.-it-should-be-retired-pub-90376

[2] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/everyones-talking-about-the-global-south-but-what-is-it/articleshow/103453914.cms?from=mdr

[3] https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37558

[4] https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/applied-and-social-sciences-magazines/north-and-south-global#:~:text=As%20terms%2C%20the%20North%20(also,were%20increasingly%20seen%20as%20pejorative

[5] https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37558

[6] https://tourismteacher.com/north-south-divide/

[7] https://apnews.com/article/what-is-global-south-19fa68cf8c60061e88d69f6f2270d98b

[8] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/everyones-talking-about-the-global-south-but-what-is-it/articleshow/103453914.cms?from=mdr

[9] https://ppr.lse.ac.uk/articles/10.31389/lseppr.88

[10] https://theconversation.com/the-global-south-is-on-the-rise-but-what-exactly-is-the-global-south-207959

[11] https://www.lse.ac.uk/international-relations/centres-and-units/global-south-unit/COVID-19-regional-responses/COVID-19-and-the-Global-South

[12] https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Japan-must-take-its-Global-South-vision-forward-in-2024

[13] https://ecfr.eu/article/what-europe-can-learn-from-japans-approach-to-the-global-south/

[14] https://tourismteacher.com/north-south-divide/

[15] https://tourismteacher.com/north-south-divide/

[16] https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Japan-aims-for-13bn-in-Global-South-investments-economic-minister

[17] https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Japan-aims-for-13bn-in-Global-South-investments-economic-minister

[18] https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Japan-must-take-its-Global-South-vision-forward-in-2024

[19] https://www.jbic.go.jp/en/information/press/press-2023/press_00102.html

[20] https://www.primecapital.com/insights/australians-are-the-richest-in-the-world/#:~:text=In%20terms%20of%20mean%20wealth,United%20States%20and%20Hong%20Kong.

[21] https://eprints.qut.edu.au/123774/1/North-In-South.pdf

[22] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-isnt-australia-moving-up-ranks-global-innovation/

[23] https://research.csiro.au/aus4innovation/australian-insurer-helps-vietnamese-farmers-though-new-technology/

[24] http://bizhub.vn/corporate-news/hillridge-msig-team-up-to-protect-farmers-in-vn_344956.html

Mr. Rachit Khosla is a seasoned strategy consulting professional with rich experience in leading and executing market entry, growth strategy and open innovation/new business creation engagements for Fortune 500 businesses, large MNCs and Govt. bodies across the Asia Pacific. He has advised clients in diverse industries including green and digital areas. Before joining IGPI, Rachit was the Country Manager at YCP Solidiance, and after that, a co-founder of Conquerem — an online B2B e-bidding platform for boutique consulting firms. Rachit is an avid traveler who has set foot in 40+ countries and lived in 4 countries.

Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI) is a premier Japanese business consulting firm with a presence and coverage across Asian markets. IGPI was established by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ) in 2007. IRCJ, a US $100 billion Japanese sovereign wealth fund, is known as one of the most successful turn-around funds supported by the Japanese government.

In 2017, IGPI collaborated with the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) to form JBIC IG, providing investment advisory services and supporting overseas investment. In 2019, JBIC, along with BaltCap, jointly established Nordic Ninja, a €100 million venture capital fund to focus on deep tech sectors such as autonomous mobility, digital health, AR/VR/MR, artificial intelligence, robotics and IoT in the Nordic and Baltic region. In 2019, IGPI established IGPI Technology to focus on the area of science and technology. The company invests in technological ventures and provides hands-on management support. The company also provides business development support towards commercialization and monetization of technologies.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

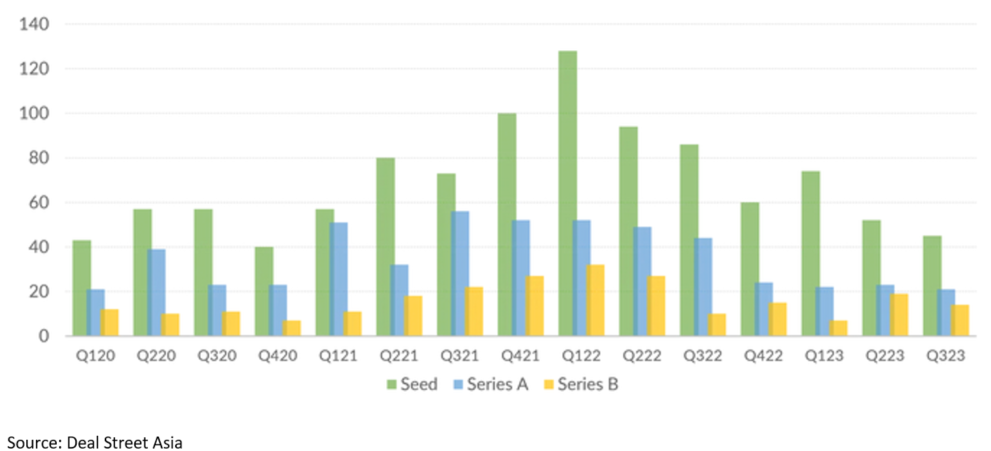

October 2023 findings from Deal Street Asia (DSA) reveal a notable shift in market dynamics, with Southeast Asian (SEA) startups navigating through the lowest quarterly deal volume in nearly three years. The third quarter, spanning July to September, witnessed only 151 deals being closed, representing a significant 27% quarter-on-quarter decline. Yearly, this translates to a substantial 34% year-on-year reduction in total deal volume and a noteworthy 52% year-on-year decrease in total deal value.

This market shift extends across early-to-later stage funding rounds. Seed-stage deals, in particular, hit a three-year low in Q3 2022, experiencing a volume drop of 44% compared to the same period the previous year. Additionally, the median value of seed rounds softened, falling by 22% over the last nine months. Similarly, Series A to Series D rounds have also encountered significant reductions. Series A deal volume faced a particularly challenging scenario in the initial nine months, while Series C witnessed the deepest correction in median value, plummeting by 59% from the same period the previous year.

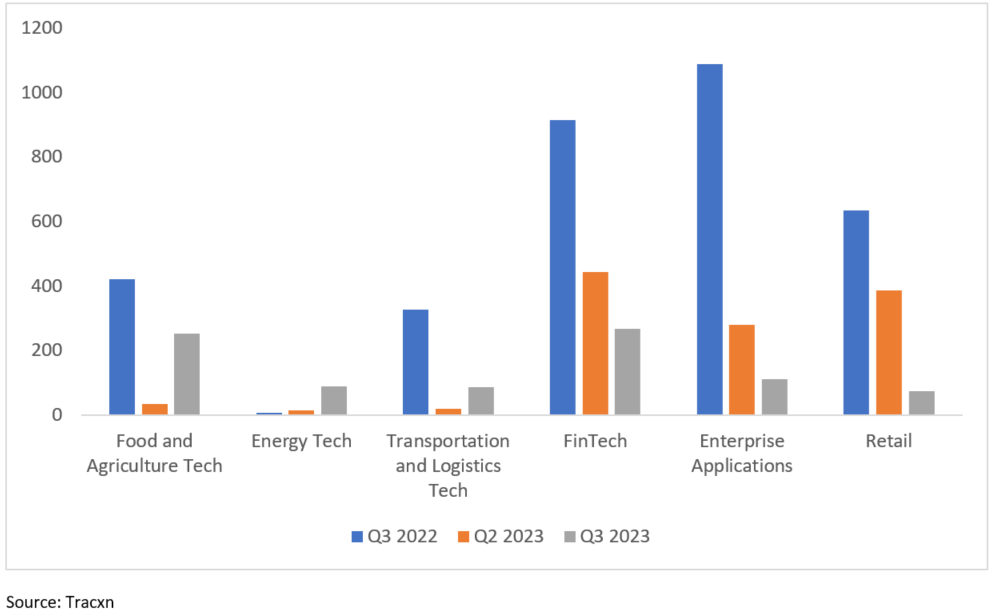

A sector-wise comparison by quarter in Southeast Asia (SEA) reveals the following trends:

In Q3 2023, the Food and Agriculture Tech sector secured funding amounting to $254 million, reflecting a growth of 638% from the $34 million raised in Q2 2023. However, this still represents a drop of 40% compared to Q3 2022. The Energy sector, on the other hand, experienced growth with funding amounting to $89 million in Q3 2023—an increase of 482% and 1014% from Q2 2023 and Q3 2022, respectively.

In 2021, there was a notable surge in startups securing funding at inflated valuations, driven by a pursuit of rapid growth and increased cash burn. However, the trajectory shifted in 2022, signaling a return to normalcy. The market experienced a decline in deal frequency, a moderation in valuations, and a rise in flat and down rounds.

While specific statistics for Southeast Asia (SEA) regarding the proportion of up, flat, and down rounds are unavailable, insights from the U.S. market provide a glimpse into this trend. Carta’s Q3 2023 report revealed that nearly one in five investments in the U.S. was characterized as a down round. The Coller Capital Global Private Equity Barometer for Summer 2023 noted that 59% of Asia-Pacific (APAC) Limited Partners (LPs) anticipate more down rounds in the next 12 months, contrasting with 24% of APAC LPs expecting fewer down rounds.

Highlighting this shift, notable instances of down rounds in SEA in 2023 include Bitkub. As reported by Asia Tech Review, Bitkub, a Thailand-based crypto exchange, attracted a $500 million investment from Siam Commercial Bank (SCB) in 2022 for a 51% stake at a valuation exceeding $1 billion. However, in July 2023, Bitkub agreed to sell a 9.22% share to Asphere for approximately $17 million, valuing the company at $184 million. This case exemplifies the recalibration in valuation dynamics and investor sentiments that have become prevalent in the evolving landscape of startup funding in the region.

Through discussions with investors, industry practitioners, and startup founders, several key reasons have been identified as contributing to the current fundraising downcycle. These include:

– Uncertainty in macro-economic conditions

The recovery in economic performance post-pandemic has been patchy, and geopolitical tensions, such as the Ukrainian-Russian war, the ongoing trade war between the US and China, and the Israel-Gaza War, have brought uncertainty to the overall economy. This has led to supply chain issues that partly contribute to the inflation we see today.

– Higher cost of funds

As a corollary to the prevailing inflation, the US Central Bank, commonly known as “The Fed,” has undertaken a series of 11 interest rate hikes since March 2022. Presently, the Fed Funds rate stands within a range of 5.25-5.5%, while the 10-year Treasury has reached its zenith at above 5%. This upswing in the cost of funds plays a pivotal role in shaping asset allocation strategies.

The escalation in the cost of funds brings forth numerous implications, among others: